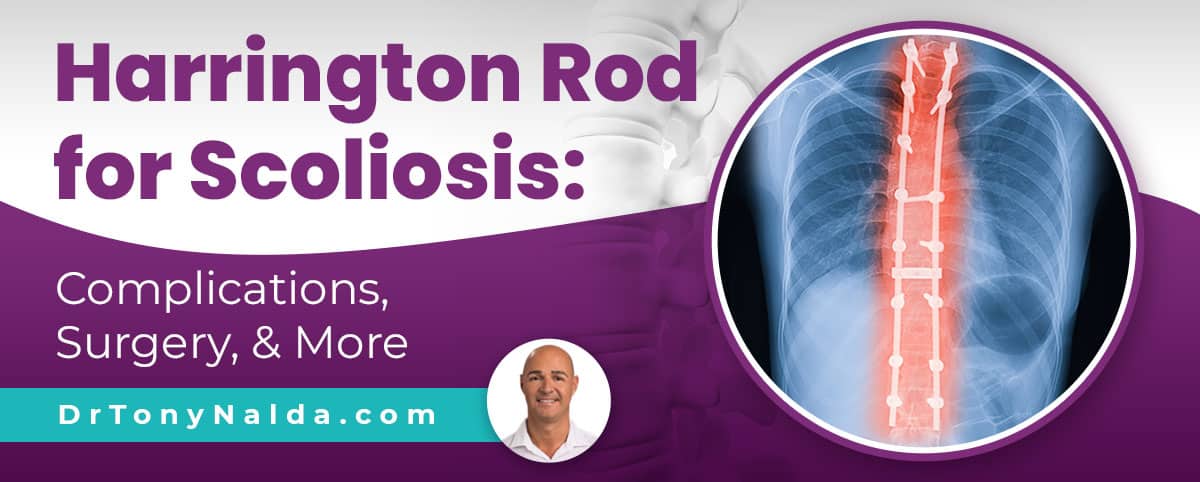

Harrington Rod for Scoliosis: Complications, Surgery, & More

There is more than one approach to treating scoliosis, both surgically and non-surgically. Just like all surgical procedures, scoliosis surgery comes with its share of risks, not to mention what it can cost the spine in terms of flexibility and range of motion.

The reality is that most cases of scoliosis can be treated non-surgically. The Harrington rod for scoliosis is hardware that’s commonly attached to the spine in spinal fusion surgery, and the procedure can come with some serious potential risks and side effects.

While not everyone is guaranteed to experience negative side effects and/or complications after spinal fusion surgery, the risk is there so should be considered carefully.

Table of Contents

What is Scoliosis?

If a person is diagnosed with scoliosis, this means they have developed an unnatural sideways spinal curve, and this disrupts the biomechanics of the entire spine.

In addition, scoliotic curves don’t just bend unnaturally to the side, they also twist, which is what makes them a 3-dimensional condition.

A measurement known as Cobb angle classifies conditions in terms of severity, and this is an important factor in determining whether or not a person is considered a candidate for spinal fusion surgery.

The higher the Cobb angle, the more tilted the vertebrae (bones of the spine) of the unnatural spinal curve are, the more misaligned the spine is, and the more likely it is to cause noticeable symptoms.

Mild scoliosis: Cobb angle measurement of between 10 and 25 degrees

Moderate scoliosis: Cobb angle measurement of between 25 and 40 degrees

Severe scoliosis: Cobb angle measurement of 40+ degrees

Very-severe scoliosis: Cobb angle measurement of 80+ degrees

Scoliosis is so often deemed a complex condition to treat not just because of the widely-ranging severity levels, but also because there are multiple types.

The condition’s most-prevalent form is adolescent idiopathic scoliosis (AIS), diagnosed between the ages of 10 and 18, so this is the form we’ll focus on for our current purposes.

The idiopathic designation means the condition isn’t clearly associated with a single-known cause, and idiopathic scoliosis accounts for approximately 80 percent of known diagnosed scoliosis cases; the remaining 20 percent is associated with known causes: neuromuscular, congenital, degenerative, and traumatic.

Now, a key characteristic of scoliosis is that it’s progressive: meaning it has it in its nature to worsen over time, particularly if left untreated, or not treated proactively.

So where a scoliosis is at the time of diagnosis is not indicative of where it will stay, and progression means the unnatural spinal curve is increasing in size, the condition’s uneven forces are increasing, and symptoms tend to become more noticeable.

Progression is what dictates surgical recommendations because it’s not until a condition progresses into the severe classification at 40+ degrees, with signs of continued progression, that patients become surgical candidates.

What is Scoliosis Surgery?

Commonly referred to as scoliosis surgery, the actual procedure is called spinal fusion, and while there are different types, commonly, the procedure involves fusing the most- tilted vertebrae at the curve’s apex into one solid bone.

Commonly referred to as scoliosis surgery, the actual procedure is called spinal fusion, and while there are different types, commonly, the procedure involves fusing the most- tilted vertebrae at the curve’s apex into one solid bone.

Fusing the bones together is done to eliminate movement in the area, meaning the vertebrae of the curvature can’t become more tilted, increasing curvature size: progression.

Rods are commonly attached to the spine to hold it in place, and this hardware is permanent.

If hardware fails, or an adverse reaction to the hardware develops, the only recourse is more surgery.

Just like all surgical procedures, spinal fusion comes with its share of potential risks, side effects, and complications, and while not all patients who’ve undergone spinal fusion will experience any of the following negative effects, the risk is there so should be considered carefully.

The Harrington rod is a common component of spinal fusion surgery, so let’s move on to the specifics of using the Harrington rod for scoliosis treatment.

What is the Harrington Rod?

The Harrington rod is a common type of hardware used in spinal fusion surgeries in the United States.

Harrington rod insertion is an aspect of spinal fusion that’s performed with the goal of stopping progression.

Harrington rod insertion is an aspect of spinal fusion that’s performed with the goal of stopping progression.

Spinal fusion is a costly, lengthy, and invasive surgical procedure that involves the use of a ratcheting system to insert the rod along the concave side (inner edge) of the scoliotic curve.

Most often, the rod is attached to the spine via two hooks: one at the top of the curve, and the other at the bottom.

Then the ratcheting system is used to stretch and straighten the unnaturally-curved spine; after the spine is stretched and straightened, the fusion takes place, and this often involves the removal of intervertebral discs that sit between adjacent vertebrae; this is so the vertebrae can be fused together into one solid bone.

However, the spinal discs perform many essential functions. They give the spine structure, provide cushioning between adjacent vertebrae, enable flexible movement, and act as the spine’s shock absorbers, so this can affect the spine in different ways.

Often, intervertebral discs that have been removed are replaced by a bone graft taken from the patient’s hip.

When successful, the rods hold the spine in a corrective position, the fusion heals, and progression is prevented, but how does the procedure affect the spine’s overall health and function, and what are some surgery risks to be considered?

Harrington Rod Surgery Results

Ideals of success can vary, and while spinal fusion can be considered a success by reducing a patient’s Cobb angle, I want patients to understand how that success can affect the fused section of the spine.

The fused section of the spine will never be able to twist and bend the way it used to; in fact, there’s an average 25-percent loss of spinal mobility post-surgery, and in addition, pain at the fusion site is a common disappointment, as is pain in other areas of the spine due to the effects of the rest of the spine having to compensate for the fused portion’s rigidity.

The number of vertebrae fused will have a large effect on the outcome. Some patients who have only had a minimum of vertebrae fused still have enough flexibility above and beyond the fused section to not notice a significant change, but others who have larger fused sections can be disappointed with these results.

In addition, a fused spine is weaker and more prone to injury, and that knowledge alone can have a significant psychological effect, causing many patients to be fearful of trying new things, and/or take part in once-loved activities.

So a spine that’s less flexible, weaker, less able to absorb force, and more prone to injury isn’t always the ideal result, and the reality is that most cases of scoliosis can be treated non-surgically.

There are also the risks associated with potential complications that occur during the procedure itself:

- Excessive blood loss

- Infection

- Nerve damage

- Adverse reaction to hardware used

So while Harrington rod for scoliosis treatment is a component of spinal fusion, and when successful, can indeed straighten a crooked spine, holding the spine in a corrective position by artificial means is not the same as actually correcting a scoliosis on a structural level.

Correcting scoliosis on a structural level means the most-tilted vertebrae of the curve have been repositioned so they are better aligned with the rest of the spine, and when combined with other forms of proactive treatment like in-office therapy to increase core strength, corrective bracing, and custom-prescribed home exercises, true corrective results can be achieved, without facing the risks of invasive spinal fusion.

Conclusion

The Harrington rod for scoliosis refers to a commonly-used hardware in spinal fusion surgery, which is a component of traditional scoliosis treatment.

Spinal fusion surgery has the end goal of preventing progression, and it does this by eliminating movement in the curved section of the spine that’s been fused, but this can cost the spine in terms of flexibility and motion.

In addition, many patients also experience an increase in back pain post-surgery, and this can be due to spinal rigidity and how the spine’s surrounding muscles are affected.

What I want patients, and their families, to understand is that there is more than one scoliosis treatment option available to them, and with a progressive condition like scoliosis, the best time to start treatment is always now.

For those who choose to forego a surgical recommendation, or who simply prefer to try a less-invasive treatment option prior to a surgical response, here at the Scoliosis Reduction Center, I treat patients with a modern conservative non-surgical treatment approach that strives to preserve as much of the spine’s natural function as possible.

Dr. Tony Nalda

DOCTOR OF CHIROPRACTIC

After receiving an undergraduate degree in psychology and his Doctorate of Chiropractic from Life University, Dr. Nalda settled in Celebration, Florida and proceeded to build one of Central Florida’s most successful chiropractic clinics.

His experience with patients suffering from scoliosis, and the confusion and frustration they faced, led him to seek a specialty in scoliosis care. In 2006 he completed his Intensive Care Certification from CLEAR Institute, a leading scoliosis educational and certification center.

About Dr. Tony Nalda

Ready to explore scoliosis treatment? Contact Us Now

Ready to explore scoliosis treatment? Contact Us Now