Can Scoliosis Be Misdiagnosed? Symptoms Explained!

The spine is a key structure of human anatomy, and as such, it's vulnerable to a number of conditions/issues developing. The spine is naturally curved for a reason, and if it loses one or more of its healthy curves, bad curves develop that disrupt the biomechanics of the entire spine.

Any condition can be misdiagnosed, and while there are a number of spinal conditions that cause a loss of the spine's healthy curves, there are a number of characteristics that set scoliosis apart, making it harder to misdiagnose, particularly once an X-ray has been performed.

As scoliosis isn't an easy condition to misdiagnose because of a number of parameters that have to be met, let's explore the nature of those parameters and what they mean.

Table of Contents

Diagnosing Scoliosis

There are a number of spinal conditions that cause a loss of its healthy curves, but what makes scoliosis different?

Scoliosis is the leading spinal deformity among school-aged children, and as such a highly-prevalent condition affecting children, there was a time when scoliosis screening was performed in schools across the United States, but that has since changed, putting the onus of early detection onto the shoulders of parents, caregivers, and patients themselves.

There are no treatment guarantees, but with early detection and intervention, there are fewer limits to what can be achieved, and to reach an official diagnosis of scoliosis, certain parameters have to be met.

There are no treatment guarantees, but with early detection and intervention, there are fewer limits to what can be achieved, and to reach an official diagnosis of scoliosis, certain parameters have to be met.

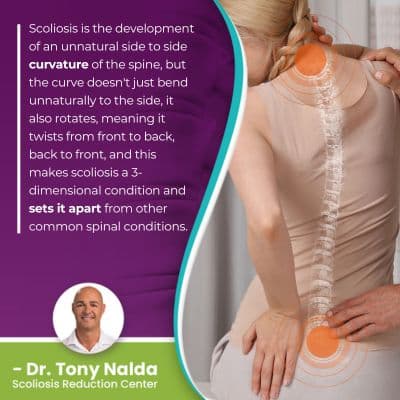

Scoliosis is the development of an unnatural side to side curvature of the spine, but the curve doesn't just bend unnaturally to the side, it also rotates, meaning it twists from front to back, back to front, and this makes scoliosis a 3-dimensional condition and sets it apart from other common spinal conditions.

In addition to a sideways-bending and rotating spinal curve, the curve also has to be of a minimum size to be considered a true scoliosis, and that's only determined through an X-ray; when you can see what's happening in and around the spine on an X-ray, those results are hard to misinterpret and misdiagnose.

Cobb Angle Measurement

A patient's Cobb angle measurement is a key piece of information that treatment plans are shaped around, and as a minimum of 10 degrees is needed to reach a diagnosis, it's a key piece of information in many ways.

A patient's Cobb angle is determined during X-ray by drawing lines from the tops and bottoms of the curve's most-tilted vertebrae, and the resulting angle is expressed in degrees.

The higher a patient's Cobb angle, the more unnaturally-tilted the vertebrae at its apex are, the more out of alignment they are with the rest of the spine, and the more severe the condition:

- Mild scoliosis: Cobb angle measurement of between 10 and 25 degrees

- Moderate scoliosis: Cobb angle measurement of between 25 and 40 degrees

- Severe scoliosis: Cobb angle measurement of 40+ degrees

- Very-severe scoliosis: Cobb angle measurement of 80+ degrees

So once a Cobb angle measurement of at least 10 degrees, and a rotational deformity is also confirmed, scoliosis can be diagnosed.

As such a complex and highly-variable spinal condition, part of diagnosing scoliosis involves further classifying conditions based on key patient/condition variables, one of which is condition severity; additional classification points include patient age, condition type, and curvature location, so let's explore why each is important.

Patient Age

Patient age is a key factor, not only because it indicates overall health and fitness, but also because it affects progression and pain.

Another condition characteristic that sets scoliosis apart is its progressive nature, meaning it's virtually guaranteed to get worse over time, and this makes it more complex to treat and its effects more noticeable.

Scoliosis affects all ages (congenital scoliosis, infantile scoliosis, juvenile scoliosis, adolescent scoliosis, and adult scoliosis), but the most prevalent type is adolescent idiopathic scoliosis, diagnosed between the ages of 10 and 18, and this age group is the most at risk for rapid-phase progression because it's growth that triggers curve progression.

So patient age tells me how much of a risk rapid progression is, and how much of a focus on counteracting progression during growth is needed in treatment.

So patient age tells me how much of a risk rapid progression is, and how much of a focus on counteracting progression during growth is needed in treatment.

Patient age also tells me whether pain management is likely to be a necessary focus of treatment or not.

Scoliosis doesn't become a compressive condition until skeletal maturity has been reached, and it's compression of the spine and its surrounding muscles and nerves that causes the majority of condition-related pain.

In young patients whose spines are still growing, the constant lengthening motion of a growing spine counteracts the compressive force of the unnatural spinal curve.

Pain is the main symptom that brings adults in to see me for a diagnosis and treatment, and this can include back pain, muscle pain, and/or pain that radiates into the extremities due to nerve compression and/or nerve root irritation.

Condition Type

There are also different condition types a person can develop, and type is determined by causation.

The majority of scoliosis cases, approximately 80 percent, are classified as idiopathic scoliosis, meaning not clearly associated with a single-known cause, and the remaining 20 percent are associated with known causes, so these types are considered atypical: neuromuscular scoliosis, congenital scoliosis, and degenerative scoliosis.

In atypical types of scoliosis, I know there is an underlying pathology causing the condition's development that complicates the treatment process.

For example, neuromuscular scoliosis is caused by the presence of a larger neuromuscular condition such as cerebral palsy, spina bifida, or muscular dystrophy, to name a few, and as the underlying cause, the neuromuscular condition has to be the focus of treatment.

Condition type is important because when known, addressing a condition's underlying cause is the best way to improve a patient's overall quality of life and minimize its symptoms.

Curvature Location

There are three main spinal sections, and each has its own characteristic curvature type and roles to play in maintaining spinal health and function.

The cervical spine refers to the neck; the thoracic spine is the middle/upper back, and the lumbar spine refers to the lower back.

Curvature location is important not only because it tells me where to concentrate treatment efforts, but also because it can indicate potential effects and complications; in most spinal conditions, it's the area of the body located the closest to an affected spinal section that's going to feel the majority of its direct effects.

For example, in lumbar scoliosis, a common complication is sciatic nerve pain; the sciatic nerve starts in the lumbar spine and extends down the back of the hip, buttock, leg, and into the foot, and if the unnaturally-curved lumbar spine compresses the sciatic nerve, symptoms can be felt anywhere along the extensive pathway of the nerve.

So if a patient with lumbar scoliosis is experiencing unexplained pain down the left side of the body, I know it's likely related to sciatic nerve compression and can factor that into treatment plans.

Conclusion

While any condition can be misdiagnosed, some are harder than others because they have characteristics that set them apart from the rest; this is the case with scoliosis.

There are a number of conditions that cause a loss of the spine's healthy curves, but a scoliotic curve doesn't just bend unnaturally, it also twists, and this is a feature that makes scoliosis a complex 3-dimensional condition, and for treatment to be effective, it has to be addressed as such.

Scoliosis is also progressive, so where it is at the time of diagnosis doesn't mean that's where it will stay, at least not without the help of proactive treatment, and this is another characteristic that makes scoliosis unique.

Here at the Scoliosis Reduction Center, the diagnostic process is lengthy and involves comprehensive assessment, making it difficult to misdiagnose; it's also much more common to be misdiagnosed by a medical professional who doesn't specialize in the condition in question.

My patients benefit from a proactive conservative treatment plan that integrates multiple scoliosis-specific treatment disciplines so conditions can be impacted on every level: chiropractic care, physical therapy, corrective bracing, and rehabilitation.

When treated proactively, surgical treatment can be avoided as many cases of scoliosis don't require scoliosis surgery.

A scoliosis diagnosis doesn't have to mean a life of limitation, nor does it have to mean giving up on one's dreams; while it's understandably deflating for patients recently diagnosed to hear that as a progression condition, there is no curing scoliosis, when addressed proactively, it can be highly treatable.

The best way to reach an early diagnosis of scoliosis is to go for a screening exam, so if postural changes are noticed, along with disruptions to balance, coordination, and/or gait, this can warrant the need for further testing and can lead to early detection, intervention, and treatment efficacy.

Dr. Tony Nalda

DOCTOR OF CHIROPRACTIC

After receiving an undergraduate degree in psychology and his Doctorate of Chiropractic from Life University, Dr. Nalda settled in Celebration, Florida and proceeded to build one of Central Florida’s most successful chiropractic clinics.

His experience with patients suffering from scoliosis, and the confusion and frustration they faced, led him to seek a specialty in scoliosis care. In 2006 he completed his Intensive Care Certification from CLEAR Institute, a leading scoliosis educational and certification center.

About Dr. Tony Nalda

Ready to explore scoliosis treatment? Contact Us Now

Ready to explore scoliosis treatment? Contact Us Now